The road to Brave 1.0

Over the past 4 ½ years I’ve been helping to build a “big” new startup named Brave.

It’s been a wild ride, far exceeding anything I could have imagined.

The company has grown from a team of 2, to over 100 passionate mission-driven teammates. Our user base has grown to 8.7 million monthly active users. Our users help support over 300,000 registered content creators via micropayments. And our community is growing and thriving more every day.

Brave 2019 company event:

Today we’re celebrating the release of Brave 1.0, and I couldn’t be happier to be a part of it.

Here’s a story of how Brave came to be, told from the perspective of one of its co-founders.

October 2013 - At the Mozilla Summit

I was employed at Mozilla at the time attending a yearly Mozilla Summit event. A Mozilla Summit is a get-together where 1,600 employees, contractors, and community leaders gather to discuss, make plans, and hack on Mozilla products like Firefox.

Within days, I would have my first interview for a new job with Khan Academy. I felt held back at Mozilla and I wanted to go into full gear mode. I’ve always found motivation in mission-driven companies, so going from a non-profit company like Mozilla to Khan Academy made sense. If I wasn’t offered a position with my first choice Khan Academy, then I’d find somewhere else to go. My mind was made up.

Before I left Mozilla though, and on the final night of the summit, I wanted to get a picture with the creator of JavaScript and co-founder of Mozilla, Brendan Eich.

I told myself that this would be the last time I would see, let alone be able to get a picture of myself with Brendan.

It took me all night to gather up the courage to ask for a picture, but I finally did it.

I ended up getting the job at Khan Academy, leveraging a coding video tutorial site I had created named Code Firefox, and crushing the take home project they’d given. Phewf! Good thing I got that picture.

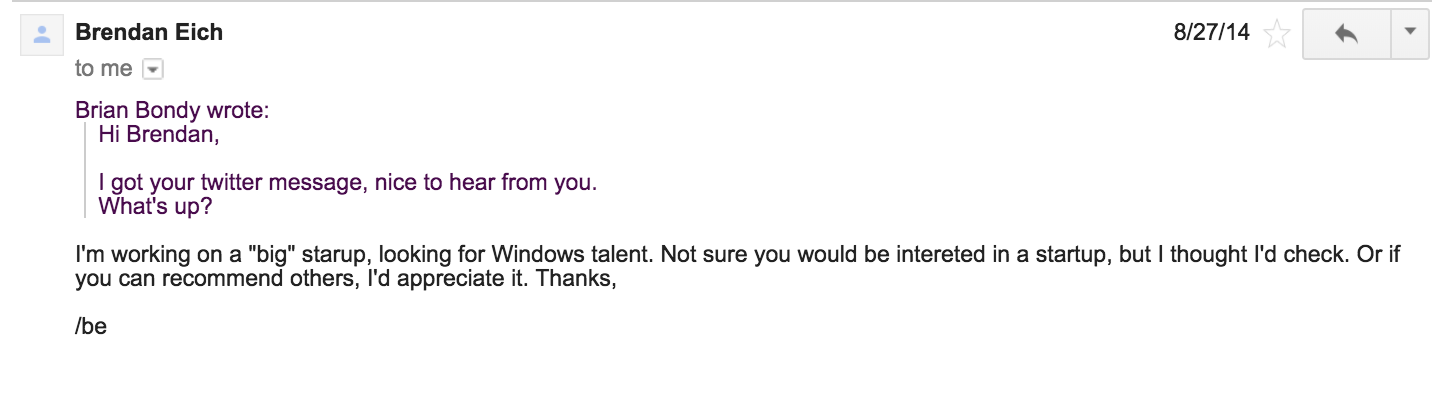

August 2014 - Surprising first contact

Nearly a year later, I was on my laptop sitting in bed. I turned to my wife and said: “Wow! The creator of JavaScript just asked me to direct-message (DM) him.”

My wife said: “He probably wants to offer you a job.”

“I don’t think so,” I said, and “I’m happy at Khan Academy anyway.”

I couldn’t DM him of course, because he wasn’t following me on Twitter at the time and his private DMs weren’t open.

I did have his personal email though, and so I started what would be a life-changing email thread.

Defining what Brave would be and how it would work

Brendan sent me an initial pitch deck for the idea of a company that would eventually be known as Brave. It wasn’t called Brave at that point, but the basic ideas haven’t changed.

- Stop allowing users to be tracked, users should own their own data.

- Speed up page load time and reduce bandwidth by blocking bad things.

- Allow publishers to get paid via cryptocurrency replacing lost revenue from the blocking.

- Allow users to get paid via cryptocurrency micropayments for their attention on privacy preserving ads.

Why me?

A lot of people like to ask why Brendan contacted me above all people. He’s probably one of the most developer-connected people on the planet.

The answer in short was that I had made it on a spreadsheet of top talent that he maintained. He didn’t originally contact me to be a co-founder, he contacted me to be a contractor because he needed top Windows talent. I’m sure he contacted several other people as well.

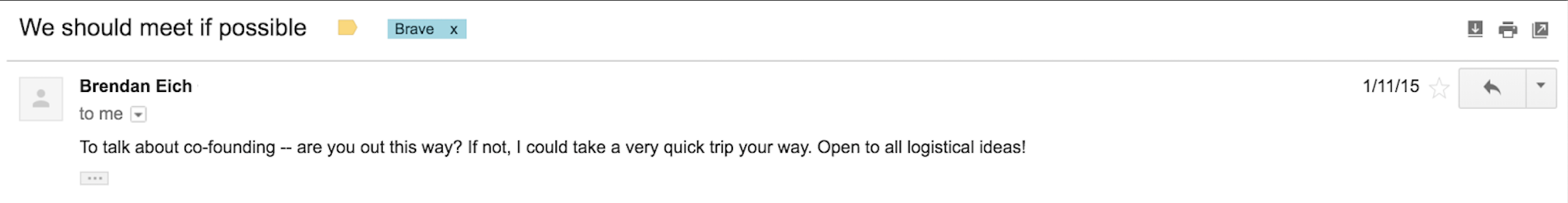

During the next 4 months of discussion, we fleshed out details of what we would build. From my previous startup experience and from creating a new browser from scratch, Firefox - Windows style enabled Metro browser. I knew exactly how a new browser could be built. I knew how installers would work, how updates would work, how signing worked, how much things would cost, how long things would take, I had the answer to various other “how” questions as well.

During this discussion, something changed. I went from being considered as a contractor with Windows talent, to being offered to be a co-founder in the company that was about to start.

May 2015 - Starting work

It took another few months to get initial funding, but in May 2015 we started this ambitious project.

I quit Khan Academy, and on my last day there, Sal Khan joked that when I made it big, I should not forget about Khan Academy and to give them a donation. I didn’t say it at the time, but I was thinking that I’d not only give a donation, but I’d help enable thousands of others to do the same.

The company was in “stealth” mode at the time, it was OK to say that I was working on a new startup, but we didn’t share Brendan’s involvement to avoid attracting media attention until we were ready. It was hard to keep it a secret, what if Brave never launched? I’d have quit my dream job and risked everything I had going for me and my family, and no one might ever know that I co-founded this company with Brendan Eich. I knew we’d have to make it work, but I also knew we couldn’t do it alone.

Our initial plan was very ambitious:

We’d build:

- Desktop browsers for Windows, macOS, Linux

- iOS browser

- Android browser

- Micro-payments for user private ads

- Built-in tracking protection

- Ad-block

- HTTPS everywhere

- Tor private tabs

- Greasemonkey type functionality.

- Extensions for other browsers (The only one we didn’t end up building)

- And more…

Thanks to Brendan being who he is, hiring was never a problem. It still isn’t. We quickly hired top talent including Yan Zhu, Brad Richter, and Marshall Rose. We built up a great set of top advisors and attracted some great talent via open-source contributions.

Picking a company name

We had a placeholder name for the company: “HyperWeb Labs”.

Brave was one of the first names we considered. But we also considered others:

- Gladiator

- Dynamo

- Superware?

Uh, no.

An advisor proposed Brownie, but I just couldn’t picture that going over well in a taskbar.

Brave was the most promising option, but we thought it might have some problems:

- Might be viewed as a bit cheesy if taken too seriously

- Boastful

- Might not be evocative of imagery / logo (Firefox was hard to beat there)

- May not translate well

Despite these potential problems though, we couldn’t come up with anything else we liked better. We decided to go with it. We did almost use “Zura” though, which is Sanskrit for Brave. We’d have used this name if we couldn’t register the company name or a domain for Brave.

Obtaining brave.com

Having the name locked in, we registered brave.io which was available for a fairly low price. We really wanted brave.com, but it had been in use for 17 years by a “nuclear polka” band founded in 1979 named Brave Combo.

I decided what the heck, I’d cold email Brave Combo anyway.

brave.com was being used and redirected to brave.com/bo. So as leverage, before I contacted them, I decided to order bravecombo.com first which was available. I reasoned that brave.com/bo isn’t much different from bravecombo.com.

I asked if they’d consider selling brave.com in exchange for bravecombo.com and a fair price. They gave a range, and after some months of convincing, we agreed on a price in that range. We’d pay half up front, and the other half 6 months later.

As a side note, Brave Combo appeared on the Simpsons and music from Brave Combo was featured on Futurama.

Getting a logo

We had 3 attempts for our logo.

The first one was from an independent contractor. Here are the initial bar napkin sketches:

We decided right there, that obviously the right direction was… the lightning bolt icon.

But after it was rendered and rasterized, we decided to go back and pick a different direction.

Our next step was to launch a crowdspring contest with a description asking for something that invoked a lion in imagery.

We kept making tweaks to it but we were never happy with it.

When Brad started working at Brave, we assigned the logo to him. He knocked it out of the park and we loved what he came up with.

Which was later revised to:

Bonus: I picked up one of the runner-up submission icons as my website logo.

First attempt at a desktop browser

The first code commit for our desktop browser was on May 10, 2015.

The code was based on Graphene, a multi-process/sandboxed web app framework built on the Gecko rendering engine, which was basically Firefox OS for Desktop. A new browser was also using Graphene at Mozilla at the time, named Firefox.html.

Firefox.html by Paul Rouget looked at the time to be the future of Firefox, with HTML to replace the user interface markup language that is still in use today, XUL. The Firefox.html project was announced Dec 6, 2014, and had a name change to browser.html, but never actually launched.

We built the UI for Brave from scratch using React and Redux: the original thinking was that we wanted more speed iterating on UI innovations. The Brave prototype found ad slots dynamically, and since we had no ad inventory at the time, comically we used a service which provided pictures of bearded men.

As you can see, the design of the browser was pre-Brad. It was done by developers that sorely needed design help.

637 code commits later, we stopped short and never released this first browser; the last commit was December 12, 2015. We realized we were still months away from building out basic platform support for things like menus, drop down lists, and other problems that Graphene had.

At this point, the company was still in stealth mode and the pressure was on for us to release something soon.

First attempt at mobile browsers

The first attempt at an iOS browser was based on React Native. It was the hot new thing, and it was just released January 2015 at React conf. The first commit on the iOS browser was on June 28, 2015 and after 116 commits, we decided that the technology hadn’t matured enough for us yet.

Since we were busy building 2 different browsers at the same time, and we had a staff of only a few, we didn’t have time to start an Android browser.

However, we used and liked a browser that was on the market, created by an independent developer named Chris Lacey. The browser was called Link Bubble.

After a lot of discussion and planning we flew Chris from Australia to San Francisco and agreed to acquire Link Bubble in August 2015. We made it free 22 days later.

The basic idea of Link Bubble was pretty good. If you’re reading an email and there’s a link you want to read, then tap the link, keep reading the email, let it load in the background in a bubble, then tap the bubble to bring up the page later. There’s no need to context switch to a new app with a loading page.

Supporting a webview from a background service was something that worked on Android, but it wasn’t officially supported. There would be a number of bugs that we couldn’t fix due to them being outside of our code base, and it had a number of limitations, like you couldn’t select text for copy and paste. It also became clear from Google statements that there was significant risk that Android would not allow background services to draw on top of other apps for security reasons in the future. We wanted a full browser, and Link Bubble would never be able to mature beyond a link reader.

Link Bubble was the company’s first product that we shipped. It gave us valuable Android experience and a user base, many of whom stuck with us.

Starting over and shipping revision 2 of everything

On the desktop side, we were in a bad spot. We were 90% there, but with missing platform support that would take us months to build. As a startup, we had limited funding and we were 7 months in. We had gathered several JS-heavy developers as our initial staff. We had a desktop browser that was built with HTML + JS. The framework the browser was based on was months away from being mature enough, but there was another framework from GitHub named Electron.

At the time, it wasn’t known that Electron wasn’t designed for building browsers, although it would later be clarified.

We knew we needed to ship, we knew Electron filled the gaps that Graphene was missing, and we knew we could port what we had to Electron. We considered switching to Chromium at this time, but we’d have likely run out of funding and never shipped if we had tried. We forked Electron into a project named Muon which was more secure by turning on sandboxing and removing Node from the renderer processes. We added extension support and made various other changes as well.

It took only 1 month and 5 days, and we were able to fill the gaps we were missing and ship the browser code base that started on Graphene with Muon. We had a beta-quality desktop browser, and while it didn’t even have bookmarks yet, on January 20th 2016, Brave went out of stealth mode and we shared our plans with the world.

The second iteration of our iOS browser was based on Firefox iOS. Firefox iOS used WKWebView but we couldn’t achieve the blocking we wanted with it, so we switched it to the older Apple-supported embeddable WebKit engine, UIWebView. This gave us the APIs we needed for Brave Shields. A month later, in February 19, 2016, we shipped our first iOS browser.

On Android, we already had something released but we needed something more robust. We weren’t in as much of a hurry but we knew a change was needed. On July 13, 2016 we settled on using Chromium, and in an unbelievable feat of engineering, 3 months later a star developer of ours named Serg had the first release ready and shipped. Our Android browser user growth was amazing, so it didn’t take long to get orders of magnitude more users than Link Bubble. We had made the right call.

Getting it right with revision 3 of everything

At this point we had created the 3 browser code bases for Android, iOS and Desktop 2 times. We had 1 more iteration in store for us.

On desktop we realized that because of the way Electron was built, it took us a long time to ship updates every time Chromium did a major upgrade. It took us 2 full time developers the entire 6 weeks of time for every Chromium upgrade. And each time we did, a lot of things were broken. Electron forked a number of files from their chromium.org versions and these forked files quickly would get out of date, leading to serious problems as Chromium progressed.

Our extension support was also lacking at the time. It took a lot of effort to support more chromium extension APIs, and they’d frequently break due to the Electron forked files. We supported a set of fewer than ten extensions, but the long tail of extensions is vitally important for growth to millions of users.

We had great success with our Android browser, so we started a new fork of Chromium built in a robust way that would be easier to rebase on top of major Chromium upgrades. We named this project Brave Core (we nearly called it Brave Heart until someone pointed out that it sounded like the 1995 film Braveheart).

Brave Core gave us full extension support, we could do Chromium upgrades very quickly, we’d improve our code sharing with Android, and things would be near bug-free. We’d see massive user growth once we were on Brave Core. We went from a browser that everyone thought they should use but didn’t always stick with or make their default instead of Chrome, to a browser that almost all users want to use all the time. Retention rates improved dramatically and user growth skyrocketed.

On iOS, we’d later reverse the decision to use UIWebView due mostly to web compatibility and crash bugs outside of our stack that we couldn’t fix and which Apple was not likely to fix. We re-forked Firefox iOS, re-added our features, and found new and creative ways to do the blocking and protection required by Brave Shields.

Android is currently nearing completion of its revision 3 rewrite, a move to the same Brave Core codebase used on desktop and mentioned above. It’ll simply be a 4th supported platform (Windows, macOS, Linux, Android) on the same code-base.

Basic Attention Token

We added tipping support first with Bitcoin and later with an ERC-20 token named Basic Attention Token (BAT). We created BAT largely with the help of a developer named Scott, as well as Marshall, on May 31, 2017. We raised 36 million dollars in under 30 seconds by selling 1B of 1.5B tokens.

The sale ended so fast that even though I tried, I wasn’t even able to buy some BAT. I remember refreshing a page to see what the current Ethereum block number was, and before the page was done loading, there was a message on Slack that said: “It’s done.”

The basic idea behind BAT is: - Users’ attention gets valued at 0 today, in fact users pay part of their dataplan or ISP bill to download trackers and ads, whereas we believe that users should be paid for their attention. They shouldn’t need to give up their privacy either like they do in today’s ad-tech. - Publishers are losing revenue and the big ad players are taking most of it. Publishers should get a bigger cut. - Ad buyers are getting poor targeting and spending fruitlessly to combat ad-fraud. They should get a better deal. - Users should be able to tip on demand, in a recurring fashion, and via anonymous automatic contributions based on their browsing, without anyone including Brave seeing their browsing history or tracking them.

From this BAT utility token sale, Brave had access to a user growth pool of funds which would be used to incentivize more users to use Brave and to support content creators.

Realizing our vision

User private ads first appeared in part thanks to work done by developers Terry and Amir on April 24, 2019 in Desktop. Luke Mulks drove early ad deals and did an amazing job by himself before we hired a sales team. Android followed, and today iOS support is also here.

Seeing things work end to end was amazing. User attention is valued, publishers are being paid, and ad vendors get the targeting they need but without tracking users.

As a company, we all feel happy and proud of what we created.

Beyond

Brave features many cool new firsts with Tor tabs, WebTorrent support, our Ethereum Remote Client MetaMask fork with Dapp detection, our blazing fast rust-based ad-block library, IPFS support via an embedded node and more.

Brave 1.0 is here thanks to the grit and hard work of hundreds of people and thousands of community members.

There’s never been a better time to download Brave.

Brave was founded to give users back the privacy and respect that they deserve. Help us prove there’s a better way to browse the Internet that puts users first and supports content creators. Get excited, enjoy the journey, we’re just getting started.