Fighting Madness - Tahoe 200

The Tahoe 200 is a 200-mile race surrounding the largest alpine lake in North America. Runners pass through aspen groves, rocky landscapes, crystal-blue lakes, dense forests, and long ridges with breathtaking views. Many say it feels like running through a painting.

At packet pick-up the night before the race, I felt strong and confident.

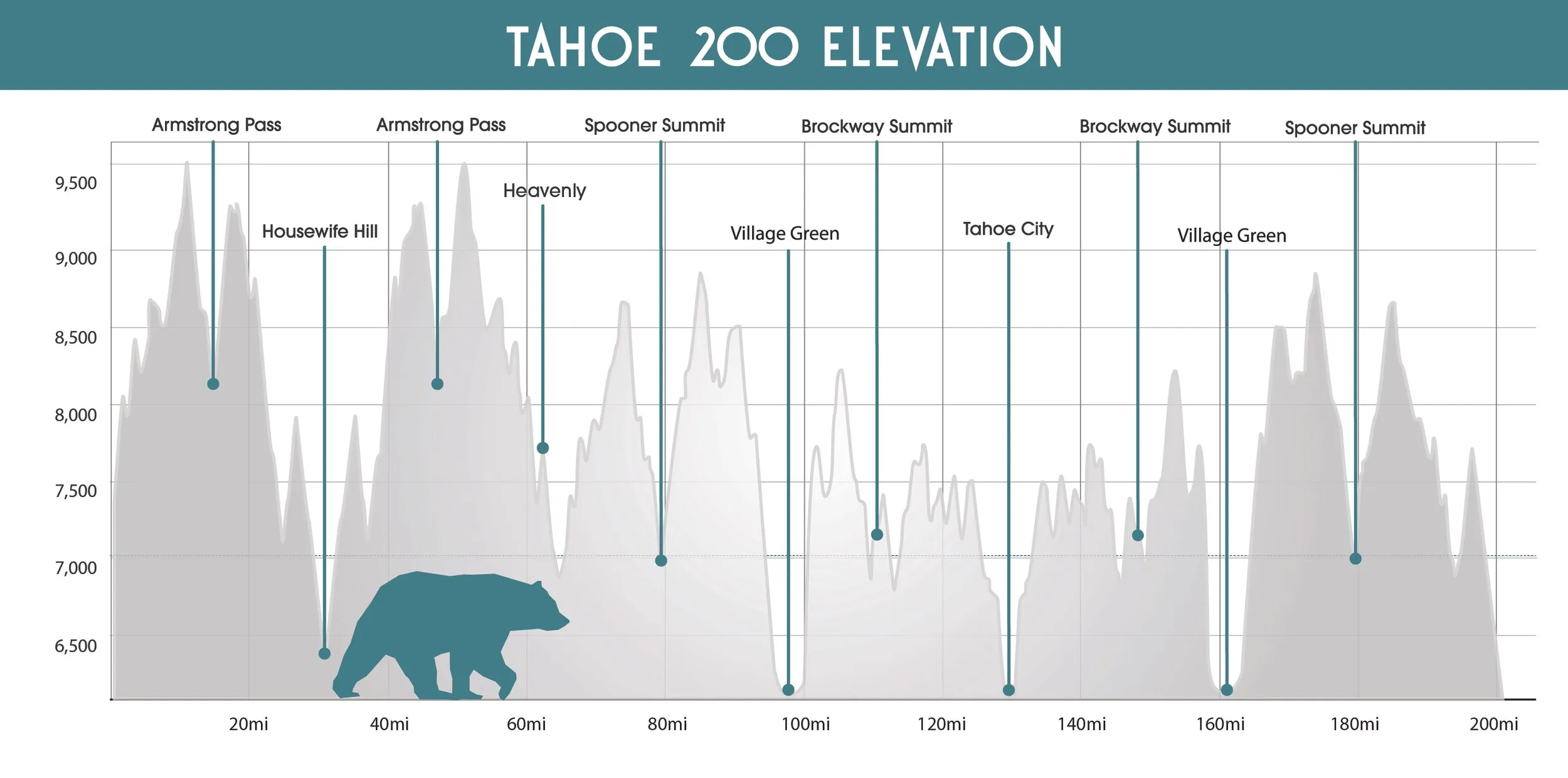

As you might expect, breathing plays a big role in a 200-mile race, especially at Tahoe. Much of the course is at high altitude, where there’s 20–30% less oxygen than at sea level. That drop can reduce your VO₂ max by 10–25%, making every climb tougher and every mile feel longer. With less oxygen available, your body relies more heavily on anaerobic metabolism, which increases lactate buildup and speeds up fatigue.

At the start line, I met up with Justin, a friend of mine also doing the race.

The scenery is breathtaking on its own, but add thin air, kicked-up trail dust, and drifting pollen, and breathing becomes genuinely difficult. “Tahoe lung” is a term runners use to describe the lung irritation and breathing issues that often show up during the race and linger for days afterward. Coughing up phlegm and wheezing are common, even for those who take precautions like wearing buffs or using Mucinex.

This race spans several days and nights, with relentless climbs and descents totalling around 37,000 feet of elevation gain and loss.

I encountered snowfields near the highest points of the course, around 10,000 feet. The race includes two out-and-backs along the south rim of Lake Tahoe, and a longer one on the north rim. The highest elevations, and most of the snow, were on the south side. I carried crampons for the first out-and-back, but decided to leave them behind on the return trip, relying on my poles alone.

This race was a relentless series of ups and downs, literally and emotionally.

This race was a relentless series of ups and downs, literally and emotionally.

After the first day, I hit a low. I couldn’t sleep at the first sleep station after finishing the south side out-and-back, so I kept going. That’s when everything started to unravel. My stomach turned on me hard, and I threw up several times. Sleep deprivation hit me just as the day reached its peak heat. I seriously considered quitting, not just the race, but ultrarunning altogether. Maybe it was time to settle for marathons and half marathons instead.

But instead of quitting, I curled up for a trail nap. And when I woke up, the despair was completely gone.

Along the trail, a strange green lichen clung to everything, trees, rocks, even the forest floor. The deeper into the race I went, the more it seemed to cover the entire landscape. Some runners believed it caused “Tahoe Lung,” but I looked into it afterward, that’s probably not true. The dust, the dry air, the altitude were the real culprits. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that the lichen was part of it. Like it had gotten into my lungs, into my thoughts. Steadily driving my sleep deprived mind mad.

Giant pine cones littered the ground, some wide and fat, others long and skinny. Most of the trails were surprisingly runnable, though rocky sections left my toes banged up. Fields of yellow wildflowers blanketed the landscape. During a check-in call home, I smashed my big toe on a rock so hard I was sure I’d broken it. It throbbed for the rest of the run.

The second and third day and night went more smoothly. I settled into a more comfortable pace and focused on enjoying the journey. I still bounced between highs and lows, especially as my lungs continued to get worse.

I had the occasional hallucination, burnt trees or oddly shaped rocks morphing into things they weren’t, but nothing out of the ordinary. Some things really stand out to you over a 200-mile distance.

At the second-to-last aid station, deep into the night, I met up with Justin and hoped he’d join me. He wasn’t feeling well, though, and needed more rest. Casey, a good friend who was crewing and pacing for Justin, was there too. I decided to push on while it was still cool out. Hours later, at the final aid station, Justin caught up and passed me.

The final 28km of Tahoe 200 was one of my darkest running experiences. I was very confused and disoriented. I wasn’t OK. It was extremely hot and I was starting to feel dehydrated. I was in an extremely sleep deprived state.

As people waited for me to complete the last 28 km section, I was on the edge of losing my mind, or perhaps beyond it.

I couldn’t remember why I was running along the route. What was I doing? What is a race? My heart pounded loudly. I was scared.

I kept asking that question as I unraveled. I couldn’t be done until I figured out why I was here. I needed to understand it. Obsessively and frantically. This wouldn’t end until I figured it out. Everything hinged on that one answer.

The life I knew couldn’t return, not until I figured it out.

My analytical brain tried to come to the rescue: You go through all the points of a defined route. That’s what makes it a race.

But it felt fake. Like someone else’s thought, stuffed into my head. I didn’t believe it. Shouldn’t there be others?

No one else was here. No one else could be. I was alone, stuck in this state.

How did they define Tahoe?! The numbers on my watch were moving too slowly. Everything looked the same. I kept turning in random directions because my watch demanded it.

I’d sprint for as long as I could, but the numbers appeared immutable.

Was I even in the race anymore? Was anyone? What if I’m doing it wrong? I will run out of water! No one was around. No one was coming. Just me. Alone. Confused.

It felt like I had slipped out of reality and into some warped imitation of it. I was trapped in a place that was built to break me.

I couldn’t go on, it wasn’t a decision. I saw a shady patch off the trail and stumbled into it in a sitting position.

Would I finish? I didn’t know. Would I wake up? I didn’t know. Nothing made sense anymore.

All I could do was shut down. I didn’t know if I was about to sleep or die, but I blacked out.

I slept.

And then, I woke up.

Not fully, but just enough. In my half-awareness, I had an enlightening thought:

To break the cycle, you needed to complete the cycle.

To finish, I need to get back to the start. My watch wasn’t leading me in circles. It was guiding me home. That was the way out. The way back to my life, my family. That’s what I had to do.

So I got up and I kept going. I knew it would be hours. But my sanity was back. I was no longer confused. I had patience, my greatest virtue. That’s how you get through these things. Patience.

With just three kilometers to go, my headphones started cutting out, and then went silent. I reached for my phone, only to find my pocket empty. It must have fallen out earlier when I stumbled and kicked a rock. I needed it for navigation; my watch wasn’t always precise enough to follow the route. So I turned around and backtracked half a kilometer. Eventually, I found it, almost completely buried in the dirt.

At the finish line, I saw my friends Justin, Sarah (Justin’s partner), and Casey waiting for me. The sight of familiar faces hit me hard, it meant the world. I stumbled across the finish line, fighting back the tears that had been building in my eyes.

You want so badly for the race to be over. But the moment it ends, it shifts, without warning, into a memory of something you’ll miss, but never forget.

“What do you want from McDonald’s?” Justin asked.

“Two fish sandwiches,” I said, instantly.

“Brian,” he groaned. “That’s a horrible way to celebrate! It’s cold and I’m tired. Don’t joke around!”

“I’m not joking,” I said. “That’s exactly what I want.”

At the finish line, I was routed to a table covered in belt buckles, each one handmade and infused with plants from the very trails I’d just crossed. I could choose a mystery buckle or take my time and pick one myself. I chose the latter. Some had pieces of that haunting green lichen, the same stuff that seemed to cover everything in the forest. I made sure not to pick one of those, and didn’t leave it to chance. That part of Tahoe I was happy to leave behind.

Casey and Sarah picked up the McDonald’s and retrieved our drop bags. Then they drove me, bags and all, back to my car. I hadn’t realized how high you had to lift your leg to get into the Jeep they’d rented.

I vowed never to do this race again… but I know myself too well to trust a vow like that.

Oh, and the two fish sandwiches? Absolutely to die for. Worth every mile.